Municipality of Bagumbayan

In the early fifties, Datu Kudanding Camsa, a Maguindanaon leader, opened a settlement on the western part of the Allah River. It was named Bagumbayan, which came from bagong bayan, which means “new town.”

Bagumbayan became one of the largest barangays of the municipality of Isulan. In November 1965, then-President Diosdado Macapagal turned Bagumbayan into a municipality by virtue of an executive order. The municipality comprised nine barangays taken from the western part of Isulan.

Datu Kudanding Camsa became the first mayor of Bagumbayan, but the municipality existed until April 1966 only. It was reverted into a barangay as a result of a Supreme Court ruling that the president of the Philippines could not create a municipality by executive order.

On June 21, 1969, Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos signed Republic Act No. 5960, recreating the municipality of Bagumbayan. A special election was conducted in November 1969, and Datu Don Ampatuan was elected mayor. In mid 1970, a conflict between Christians and Muslims broke out, and Vice Mayor Martin Forro became the acting municipal mayor.

Municipality of Palimbang

Palimbang used to be called Pula, after the trees that grew abundantly along the river in the area. The inhabitants of Pula were mostly Maguindanaons, who became Muslims when Sharif Kabungsuan came to Mindanao in the 1500s.

The name of the place was changed to Palimbang when some fishermen from Indonesia had to dock on Philippine shores due to bad weather. The natives, headed by Sendale Tambuto, met the foreigners and learned that they came from Palembang, Indonesia. The interaction with the visitors inspired the natives to adopt the name Palimbang as the official name of their place.

Through Executive Order No. 350, dated August 14, 1959, Pres. Carlos P. Garcia created the municipality of Palimbang. The municipality comprised some portions of Kiamba, Cotabato (now Kiamba, Sarangani), and some portions of Lebak, Cotabato (now Lebak, Sultan Kudarat).

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

A Guide to Kulaman Plateau and Its Manobo People, Lost Burial Jars, and Hundred Caves

Monday, November 30, 2015

Brief Histories of Bagumbayan and Palimbang

Friday, November 27, 2015

My Own Kelepi

The bag is made of three different native materials.

As told in previous posts, I was informed while I was in Kulaman village that I was one of the five finalists in the inaugural F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. I wanted a few things tribal to wear with my black long-sleeved shirt, skinny brown pants, and brown leather shoes, so I bought a tubaw (head scarf) and a kelepi (small sling bag made of native materials). The tubaw is simply a square plaid cloth that is mostly red. It’s a common item among the indigenous and the Islamized people of Mindanao. The kelepi is more interesting, and it will be the focus of this post.

I asked my mother to identify the materials that the bag is made of. She said that the main material is pawa, a kind of native bamboo, which is much smaller than regular bamboo. The black strips interweaved with the brown bamboo strips are nito, a vine that grows in forests. No paint, varnish, or any artificial coloring was used in my kelepi. The sling is made of abaca, a tree that looks like a banana and whose bark yields a very strong kind of fiber. The fiber used for the sling is braided. Pawa, nito, and abaca are Hiligaynon terms because it is the first language of my family. Unfortunately, I don’t know yet the counterparts of those terms in the Dulangan Manobo language.

I loved the kelepi since the first time I saw a sample of it. Weaving one obviously takes time and requires skill. When I learned from my mother how the craftsman has to make use of three different raw materials, I appreciated the output even more. The kelepi is now one of my most-prized possessions. I consider it more precious than the black leather wallet and the modern gadgets that I keep inside it.

Definitely a work of art, the bag itself is as valuable

as the things that Manobos put inside it.

Even the minimalist back part looks exquisite.

The cover is snug-fit even without a zipper or a strap.

As told in previous posts, I was informed while I was in Kulaman village that I was one of the five finalists in the inaugural F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. I wanted a few things tribal to wear with my black long-sleeved shirt, skinny brown pants, and brown leather shoes, so I bought a tubaw (head scarf) and a kelepi (small sling bag made of native materials). The tubaw is simply a square plaid cloth that is mostly red. It’s a common item among the indigenous and the Islamized people of Mindanao. The kelepi is more interesting, and it will be the focus of this post.

I asked my mother to identify the materials that the bag is made of. She said that the main material is pawa, a kind of native bamboo, which is much smaller than regular bamboo. The black strips interweaved with the brown bamboo strips are nito, a vine that grows in forests. No paint, varnish, or any artificial coloring was used in my kelepi. The sling is made of abaca, a tree that looks like a banana and whose bark yields a very strong kind of fiber. The fiber used for the sling is braided. Pawa, nito, and abaca are Hiligaynon terms because it is the first language of my family. Unfortunately, I don’t know yet the counterparts of those terms in the Dulangan Manobo language.

I loved the kelepi since the first time I saw a sample of it. Weaving one obviously takes time and requires skill. When I learned from my mother how the craftsman has to make use of three different raw materials, I appreciated the output even more. The kelepi is now one of my most-prized possessions. I consider it more precious than the black leather wallet and the modern gadgets that I keep inside it.

Definitely a work of art, the bag itself is as valuable

as the things that Manobos put inside it.

Even the minimalist back part looks exquisite.

The cover is snug-fit even without a zipper or a strap.

Thursday, November 26, 2015

Winning at the F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards

From left to right: National Artist Bienvenido

Lumbera, me (honorable mention), L. A. Piluden (honorable mention), Dominic

Paul Sy (third prize winner), Joshua Carlo Pile (second prize winner), the father of Joy Anne Icayan (first prize

winner), and National Artist F. Sionil Jose (Photo taken from FSJ’s Facebook

account)

Exactly a month ago today, I won at the F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. Receiving honorable mention in the awards is perhaps the best thing that happened to my writing life this year. I’m not just talking about the award itself. Many other things happened in my three-day trip to Manila. I met old friends, learned of good news about the manuscript of my novel, had a three-hour lunch with National Artist F. Sionil Jose himself, and went to a museum and a gallery to see Kulaman Plateau burial jars.

“Day of Mourning,” the story that I submitted for the awards, is about the Mamasapano incident. Forty-four members of the Special Action Forces of the Philippine National Police were killed in the encounter, and the news outraged many Filipinos. My story, however, is not about the police officers. It’s told from the viewpoint of a Maguindanao woman whose son is a separatist rebel and may or may not have been killed in the skirmish. I remember being quite depressed right after writing the story. I felt that I had created something beautiful, but I was disconcerted that it was borne out of something that shouldn’t have happened at all.

I learned on October 26, during the awarding, that the organizers received 176 entries, all from Filipino aspiring writers who were thirty years old or younger, since only those who belonged to the age group could join. The three judges pared down the entries to twenty-two, from which they were supposed to choose the top three only. In a conversation after the awarding, one judge told me and the other winners that the judges decided to choose five finalists, and the organizers—the family of F. Sionil Jose—agreed. That’s how another writer and I came to receive honorable mention and ten thousand pesos each even if such awards were not included in the original call for submissions. And as promised, the top three winners received fifty, thirty, and twenty thousand pesos respectively.

I had not known before the awarding what specifically the place of my story was. I was just told that I was one of the five finalists and I should pack my bags because I was getting a free round-trip flight to Manila and a two-night stay in a hotel. It was a workshop mentor of mine who broke the news to me, rather accidentally. She congratulated me a few moments after I entered the library of De La Salle University, the venue of the awarding. I thanked her and said, “But I don’t really know if I’m a finalist or what.” She said, “It’s in the program.” I opened the glossy yellow paper that had been given to me at the entrance, and on it I saw my name—the fourth one from the top.

I love the certificate that I received—minimalist, black and white, onionskin.

My literary mentor had left by this time. Perhaps she had been afraid that I would be devastated to find out that I had not won the first prize, and she had not wanted to see me cry. I felt the opposite, though. I was delighted to receive honorable mention because it meant that I would have two honorable mentions this year; the month before, another story of mine had been included in the shortlist of six in the Nick Joaquin Literary Awards. I like it when good things come in twos. That’s why I always buy an extra copy whenever I see a notebook that I like and my account name in social networks is rj2ortega. The obsessive-compulsive in me might not have been very happy had I gotten a citation in one award and then a numbered place in another award. Besides, I had prepared myself for whatever that would happen in the F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. In the hotel, I had told myself to be just thankful for whatever would be given to me because judges—and publishers, editors, critics, and ultimately readers—owed me nothing. If they appreciated my work, I would be thankful. If they didn’t, it would hardly matter; I had long discovered that I could not simply make myself stop writing. The only worry I had about not getting into the top three was that I would not have extra money to buy the books (and burial jars) that I might want to buy while in Manila, and it turned out that I had nothing to worry at all, for the honorable mention came with a cash prize. I was given an envelope right after the awarding.

The ceremony was short, maybe thirty minutes only. F. Sionil Jose and another national artist for literature, Bienvenido Lumbera, gave the certificates to the winners. What surprised me most was that F. Sionil Jose was visibly touched by the thirty-second acceptance speech that I gave, and I didn’t learn of what happened until days later, when I was already home and browsing Facebook about the event. A member of the audience posted on Facebook that my “words brought tears to Manong Frankie’s eyes.” I wasn’t able to see the national artist because he was behind me on the stage while I was speaking. But I remember that after the awarding, one of his daughters approached me and said that my speech had made her cry. To be honest, I thought she was just pulling my leg. I felt that my speech was for writers who had spent a life of sacrifices for the craft, and as far as I knew, the children of F. Sionil Jose went on to have successful careers but not as a fictionist like their father. Everything made sense to me after I read the Facebook post. F. Sionil Jose’s daughter must have cried because she saw her father cry on stage. My speech wasn’t earth-shaking or anything, but I spoke from the heart:

A few years ago, I decided to spend the rest of my life writing stories, and I believe I don’t have to tell the people here how difficult it is to stand by that decision. This award reminds me that I’m on the right path, that I’m doing the right thing. Thank you to National Artist F. Sionil Jose and his family and Philippine PEN. I am so honored and grateful. I will keep on writing, Sir Frankie. Madamo gid nga salamat.What happened after the ceremony was a delightful swirl. TV5 took a video of us winners with F. Sionil Jose. The news came out on television a day after, and it can be seen on YouTube. Manila Bulletin also interviewed us and took our photos, individually and as a group, but as of this writing, the article has not come out yet. L. A. Piluden of Benguet (honorable mention) and Dom Sy of Quezon City (third prize winner) were really nice. I believe I struck an instant friendship with them. A professor approached me and said encouraging things about “Rajah Muda,” my novel manuscript. She was a judge in a competition to which I submitted the manuscript, and though the judges were not told of the identity of the authors, she later found out that the manuscript was mine because she was a staff in another competition to which I submitted the same manuscript. My work didn’t win in either competition, but she told me that in the competition that she judged, my manuscript was close second to the winner. (I learned weeks later from another judge that on the second deliberation of the judges, they were just choosing between my work and the eventual winner and it was like “choosing between a polished jade and a rough diamond.” The jade won. But a diamond is a diamond. It’s just waiting to be polished!) I was glad to find out that I had not wasted the eight months of my life that I had spent on that project. The director of a university press also approached me and said that the press would publish “Rajah Muda,” which I had submitted to the press a month or so earlier. I’m not naming, though, award-giving bodies and educational institutions here because the news given to me were not official.

That evening, I had dinner in Malate with Jake and Reno, two of my co-fellows at the 53rd Silliman University National Writers Workshop. Jake, who lives in Makati, had gone that morning to the office of the Philippines Graphic to get for me my Nick Joaquin certificate and copies of my two stories that appeared in the magazine the previous year. I felt like a child who was given free toys.

The next day, my fellow winners L. A. and Dom and I had a three-hour lunch with Manong Frankie and Manang Tessie, his wife. We first met in Solidaridad, the bookshop that the Jose family owns, and then we ate in an Indian restaurant nearby, and then we walked back to the bookshop. At 91 years old, the national artist is still so full of energy when he talks. He told us at the outset to ask him questions about writing because he wanted to share or pass on to us his personal views and techniques on the craft. We were no longer so intimidated by him this time because the previous day, he had showed us the F. Sionil Jose Collection in the La Salle library, which contains his own books, his drafts, and one hundred of his favorite books by other authors. I was already familiar with most of what Manong Frankie said, for I had read interviews of him and I had also been studying on my own how to be a good fiction writer. What struck me most among the things that he said was this advice: “Use folk tales and ennoble them.” He said this was what Homer and Yeats did. I realized that this was what I had been trying to do and this was what I wanted to do. The advice is now at the top of my pantheons of advices, along with Butch Dalisay’s “Push the narrative,” which he said while critiquing my story at the 20th Iligan National Writers Workshop.

Manong Frankie has to walk with a cane and needs some assistance, so on our way to and from the Indian restaurant, he held on to my arm. That gave me a chance to ask him a few more questions. I asked him if he had a secret diet. He said, “Nothing. I eat anything.” I also asked him some things about politics, but I won’t quote here his answers. If you’re familiar with the man, you probably know that his views sometimes cause tempers to flare. When we returned to Solidaridad, he pointed to the shelf at the counter where his books were displayed. “Choose two books, each of you,” he told my fellow winners and me. I was ecstatic. I had prepared for it! Earlier, before meeting Manong Frankie upstairs, I had reserved copies of the American edition of the five-part Rosales Saga, the most famous of Manong Frankie’s works. Dusk costs nearly one thousand pesos and is the most expensive. The Samsons and Don Vicente cost nearly five hundred pesos each and contain two books each. So when Manong Frankie made us choose two books that we could have for free, I presented The Samsons and Don Vicente. He didn’t seem to mind that I was being wise. In fact, he decided to give us more. L. A., Dom, and I also received a copy each of Short Stories, which contains works that are “culled from the author’s five volumes of short fiction.” Needless to say, the books were all autographed.

I now have the complete five-part Rosales Saga and the best stories of F. Sionil Jose, and three of these four autographed books are gifts from the National Artist himself.

I could spend a whole day just listening to F. Sionil Jose. Unfortunately, we had to bid goodbye to him at about three in the afternoon. L. A. had to travel back to Baguio, Dom had a class in UP Diliman, and I had to meet Reno to see with him the limestone burial jars in Museum of the Filipino People and in a private gallery in Intramuros. I can’t name the gallery for now and my posts about my trip there won’t be online until late next year because I’m wary of making the information public. I don’t want to help spread the news that the Kulaman Plateau artifacts can be openly bought as though they’re ordinary gadgets. I’m hoping for a miracle to happen in the next few months and for the jars to be returned to their original home.

Reno and I spent the evening in Makati with Camille, who was also a fellow at the 53rd SUNWW. I would commit a literary sin if I forgot to mention that Camille had “workshopped” the story that I submitted to the F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. My win is partly due to her careful reading of my draft and incisive comments. Jake also joined us every now and then, like a butterfly in a garden. We hanged out in a 24/7 convenience store and decided to spend the whole night talking. I guess we truly missed one another; it was our first time to meet in person after a year and a half, after the workshop. I gave them Dulangan Manobo trinkets that I had bought from Kulaman Plateau. When morning came, I headed straight to the airport, taking home with me my honorable mention certificates, my signed copies of F. Sionil Jose’s books, my photos of Kulaman jars in Manila, and a couple of intangible things that I kept in my mind and heart.

On my plane to Manila, I had a good view of Mt.

Matutum despite the haze from Indonesia. I also had a glimpse of Mt. Apo. On my

way back, I had a close and clear look of Taal lake and volcano.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

How to Get to Davao Museum

If you want to see the Kulaman Plateau burial jar in Davao City, the first thing you must remember is that Davao Museum, where the jar can be found, is different from Museo Dabawenyo. The former is privately owned and is located in Zonta Building, 113 Agusan Circle, Insular Village 1, Lanang, Davao City. The latter is run by the local government and is near the city hall.

My friend Gracielle, who divides her time between Cotabato City and Davao City, served as my tour guide when I visited Davao Museum. I don’t know my way around Davao myself, so I can’t tell you how to get to Insular Village from any point in the city. But below is a photo of the entrance of the subdivision. That’s where we got off the jeepney that we were riding. If you’re taking a taxi or you have your own ride, I think you may enter the subdivision. Just have your name registered and get a visitor’s ID at the guardhouse.

From the gate, walk for some twenty meters, turn right, walk for some fifty meters, turn left, and then walk for some one hundred meters. To your right is the whitewashed Davao Museum, which occupies the whole area of the two-story Zonta Building. The Kulaman jar is in the Carlos O. Dominguez Jr. Gallery, on the second floor. It is displayed with other burial artifacts, such as wooden grave markers from Sulu and pottery from Gigantes Island and Samal Island.

The limestone burial jar most likely came from Barangay Salangsang, Municipality of Lebak, Province of Sultan Kudarat. I read somewhere before that it was donated by the Ayala Museum. This must be true, because according to a marker near the entrance of the museum, the benefactors of the museum are two Zobel de Ayala dons. The Ayalas co-sponsored the burial jar exploration that was conducted in Salangsang in 1960s by anthropologists who were connected with Silliman University. Some of the jars were given to the university’s museum, in Dumaguete City, and the better-looking ones were taken to the Ayala Museum, in Makati City. The best thing about the jar in Davao Museum is that it is shaped like many of Kulaman Plateau jars. When you see it, you get a glimpse of everything else.

My friend Gracielle, who divides her time between Cotabato City and Davao City, served as my tour guide when I visited Davao Museum. I don’t know my way around Davao myself, so I can’t tell you how to get to Insular Village from any point in the city. But below is a photo of the entrance of the subdivision. That’s where we got off the jeepney that we were riding. If you’re taking a taxi or you have your own ride, I think you may enter the subdivision. Just have your name registered and get a visitor’s ID at the guardhouse.

From the gate, walk for some twenty meters, turn right, walk for some fifty meters, turn left, and then walk for some one hundred meters. To your right is the whitewashed Davao Museum, which occupies the whole area of the two-story Zonta Building. The Kulaman jar is in the Carlos O. Dominguez Jr. Gallery, on the second floor. It is displayed with other burial artifacts, such as wooden grave markers from Sulu and pottery from Gigantes Island and Samal Island.

The limestone burial jar most likely came from Barangay Salangsang, Municipality of Lebak, Province of Sultan Kudarat. I read somewhere before that it was donated by the Ayala Museum. This must be true, because according to a marker near the entrance of the museum, the benefactors of the museum are two Zobel de Ayala dons. The Ayalas co-sponsored the burial jar exploration that was conducted in Salangsang in 1960s by anthropologists who were connected with Silliman University. Some of the jars were given to the university’s museum, in Dumaguete City, and the better-looking ones were taken to the Ayala Museum, in Makati City. The best thing about the jar in Davao Museum is that it is shaped like many of Kulaman Plateau jars. When you see it, you get a glimpse of everything else.

The entrance to Insular Village

My friend Gracielle, a nurse who writes essays, in front of Davao Museum

Because the lighting is controlled inside the

museum,

you can barely discern the flutings on the Kulaman

jar. For a clearer

image, check out this booklet.

Kulaman Jar in Davao Museum

The limestone burial jar in Davao Museum has no

label, but I know

a Kulaman jar when I see one.

I was in Davao City the previous weekend for the 6th Philippine International Literary Festival. I was one of the three speakers on the topic “New Mindanawon Writings.” I just pretty much talked about myself, which on hindsight is quite embarrassing, so I’m not going to dwell on it. Besides, the speaking engagement isn’t closely related to the topic of this blog. What I’m going to share here instead is my side trip to Davao Museum, the collection of which includes—dun, dun, duuun—a limestone burial jar from Kulaman Plateau!

Gracielle, a co-fellow of mine in two writers workshops, went with me to Insular Village, where the museum is located. The museum is small, just two-story high, but quite swanky. You would be surprised to find out that it was “inaugurated and blessed” in 1977, as a marker near the entrance indicates. Freshly painted, or just well preserved, it doesn’t have the musty smell or eerie feel of most museums. The ground floor has a broad collection of Mindanao traditional textiles, and the second floor has motley of Mindanao artworks and artifacts. I wasn’t really able to inspect each item and take in its beauty. My mind had nothing in it but the burial jar from Kulaman Plateau. Before I went to Davao Museum, I had known that the place has a Kulaman jar, so when I entered the door, all I wanted was to find the jar, examine it as closely as I could, and take photos of it for this blog. The same thing happened to me last month in Manila, when I visited the Museum of the Filipino People and a private gallery in Intramuros.

The jar in Davao Museum is a typical example of a Kulaman Plateau burial jar. The body is quadrangular. The lid is flat and square at the base, on which stands a phallic handle, but the sexual design is not obvious because the upper half of the tip is broken and missing, or at least to my eyes. The entire body and lid of the jar is covered with simple vertical flutings.

The item in Davao is the quintessential Kulaman jar.

The jar is in a display case with other burial artifacts, such as wooden grave markers from Sulu and clay vessels from Gigantes Island and Samal Island. There is no label below or beside the limestone jar, but I’m sure that it’s from Kulaman Plateau because it is stated so in a booklet inside the museum. Treasures of the Davao Museum has a photo of the jar on page 83, and the caption states that “the funerary vessel . . . is from Kulaman, Sultan Kudarat” and “its angular body and its cover with an elongated handle are made of limestone.” It didn’t occur to me to ask if the booklet is for sale. It may be, for it is displayed with local history books that are for sale. To digress a little, I bought a copy of Macario Tiu’s Davao: Reconstructing History from Text and Memory, which contains a section about the Kulaman Manobos of Davao. Tiu says that the tribe must be related to the Dulangan Manobos of Kulaman Plateau. Isn’t that interesting? I have yet to read the section and the entire book fully, though, so I can’t write about the topic in this blog until next year.

I’m thankful to the National Book Development Board for inviting me as one of the sixty-plus speakers in the two-day literary event. I got a two-night accommodation in the swanky Seda. Truth be told, I was hesitant to accept the invitation. I prefer writing to talking about writing any day. My primary motivation in going to Davao was the chance to see a Kulaman jar without spending so much. But I’m not saying that I didn’t enjoy the event. I mighty did. I got the chance to buy Macario Tiu’s Davao and Butch Dalisay’s Killing Time in a War Place and have those books signed by the authors. I was reunited with some of my mentors, friends, and younger brothers in writing. I met for the first time some familiar names in Philippine literature. And of course, I learned a lot from listening to them.

The Kulaman jar in Davao Museum is displayed

with wooden grave markers and clay vessels.

Monday, November 23, 2015

Brief Histories of Isulan and Esperanza

Municipality of Isulan

The present territories of Isulan formerly belonged to the municipalities of Koronadal (now capital and component city of South Cotabato) and Dulawan (now Datu Piang, Maguindanao).

The municipality of Koronadal, Cotabato, was created under Executive Order No. 82, dated August 8, 1947, by Pres. Manuel L. Roxas. On March 10, 1953, a portion of Koronadal became the municipality of Norala, Cotabato, by virtue of Executive Order No. 572.

On August 30, 1957, a portion of Norala was joined with a portion of Dulawan, Cotabato, to compose the municipality of Isulan. Executive Order No. 266 of Carlos P. Garcia made it possible. Kalawag became the seat of government, and Datu Suma Ampatuan was appointed as the first mayor on September 12, 1957. The name Isulan came from the Maguindanaon term isu-silan, which means “advance.” It is said to be the battle cry of a local chieftain against the invading forces of a sultan.

On June 21, 1969, President Marcos signed Republic Act. No. 5960, creating the municipality of Bagumbayan. The law cost Isulan more than 85 percent of its original land area—from 336,000 hectares to 49,551 and from 48 barrios to 17.

On November 22, 1973, Presidential Decree No. 341 was issued, dividing the province of Cotabato into Sultan Kudarat, Maguindanao, and North Cotabato. Isulan was made capital town of Sultan Kudarat.

Municipality of Esperanza

By virtue of Presidential Decree No. 339, dated November 22, 1973, the Municipality of Esperanza was created from 27 of the 34 barangays of Ampatuan, Cotabato. However, due to a petition submitted by prominent leaders, Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos issued PD 596 on December 3, 1974, reducing the area to the present 19 barangays.

Esperanza is a Spanish term that means “hope.” It is said that when Christian migrants from the Visayas settled in the area, the first baby born of them was a girl. She was baptized “Esperanza,” and the people adapted the name for the settlement, for it signified peace, unity, and progress.

Sometime in 1952, a group of Christian settlers established the sitio of Esperanza in Villamor, a barrio of Dulawan, Cotabato (now Datu Piang, Maguindanao). In 1956, sitio leader Silverio Africa requested for a government survey to turn the settlement into a barrio. The request was granted and Esperanza became a barrio, independent of Villamor. Africa became the first barrio lieutenant, or delegado.

In 1956, Datu Into Saliao, a prominent Maguindanaon chieftain, distributed land to the people by lease, share system, and even donation to those who were close to him. Esperanza and the neighboring barrios flourished, and the residents wrote a petition to the government to turn the area into a municipality, independent of Dulawan. By virtue of Republic Act No. 2509, which was enacted and approved into law without executive approval on June 21, 1959, the municipality of Ampatuan was created.

Ampatuan was inaugurated on August 8, 1959, with Datu Abdullah Sangki as the first municipal mayor. The Christian and Muslim inhabitants co-existed harmoniously for almost two decades, until 1971, when tribal conflicts erupted.

In the November 1971 election, no Maguindanaon filed candidacy, so the elected municipal officials of Ampatuan were all Christians. They held office in Barrio Esperanza.

On November 22, 1973, then-President Ferdinand E. Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 339, creating the municipality of Esperanza. The incumbent officials of Ampatuan were appointed as first officials of Esperanza. Villamor, which used to have jurisdiction over Esperanza when Esperanza was still a sitio, became one of the barangays of the new municipality.

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

The present territories of Isulan formerly belonged to the municipalities of Koronadal (now capital and component city of South Cotabato) and Dulawan (now Datu Piang, Maguindanao).

The municipality of Koronadal, Cotabato, was created under Executive Order No. 82, dated August 8, 1947, by Pres. Manuel L. Roxas. On March 10, 1953, a portion of Koronadal became the municipality of Norala, Cotabato, by virtue of Executive Order No. 572.

On August 30, 1957, a portion of Norala was joined with a portion of Dulawan, Cotabato, to compose the municipality of Isulan. Executive Order No. 266 of Carlos P. Garcia made it possible. Kalawag became the seat of government, and Datu Suma Ampatuan was appointed as the first mayor on September 12, 1957. The name Isulan came from the Maguindanaon term isu-silan, which means “advance.” It is said to be the battle cry of a local chieftain against the invading forces of a sultan.

On June 21, 1969, President Marcos signed Republic Act. No. 5960, creating the municipality of Bagumbayan. The law cost Isulan more than 85 percent of its original land area—from 336,000 hectares to 49,551 and from 48 barrios to 17.

On November 22, 1973, Presidential Decree No. 341 was issued, dividing the province of Cotabato into Sultan Kudarat, Maguindanao, and North Cotabato. Isulan was made capital town of Sultan Kudarat.

Municipality of Esperanza

By virtue of Presidential Decree No. 339, dated November 22, 1973, the Municipality of Esperanza was created from 27 of the 34 barangays of Ampatuan, Cotabato. However, due to a petition submitted by prominent leaders, Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos issued PD 596 on December 3, 1974, reducing the area to the present 19 barangays.

Esperanza is a Spanish term that means “hope.” It is said that when Christian migrants from the Visayas settled in the area, the first baby born of them was a girl. She was baptized “Esperanza,” and the people adapted the name for the settlement, for it signified peace, unity, and progress.

Sometime in 1952, a group of Christian settlers established the sitio of Esperanza in Villamor, a barrio of Dulawan, Cotabato (now Datu Piang, Maguindanao). In 1956, sitio leader Silverio Africa requested for a government survey to turn the settlement into a barrio. The request was granted and Esperanza became a barrio, independent of Villamor. Africa became the first barrio lieutenant, or delegado.

In 1956, Datu Into Saliao, a prominent Maguindanaon chieftain, distributed land to the people by lease, share system, and even donation to those who were close to him. Esperanza and the neighboring barrios flourished, and the residents wrote a petition to the government to turn the area into a municipality, independent of Dulawan. By virtue of Republic Act No. 2509, which was enacted and approved into law without executive approval on June 21, 1959, the municipality of Ampatuan was created.

Ampatuan was inaugurated on August 8, 1959, with Datu Abdullah Sangki as the first municipal mayor. The Christian and Muslim inhabitants co-existed harmoniously for almost two decades, until 1971, when tribal conflicts erupted.

In the November 1971 election, no Maguindanaon filed candidacy, so the elected municipal officials of Ampatuan were all Christians. They held office in Barrio Esperanza.

On November 22, 1973, then-President Ferdinand E. Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 339, creating the municipality of Esperanza. The incumbent officials of Ampatuan were appointed as first officials of Esperanza. Villamor, which used to have jurisdiction over Esperanza when Esperanza was still a sitio, became one of the barangays of the new municipality.

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Friday, November 20, 2015

Manobo Trinkets for Sale

Display in Delesan Kailawan, a place run by RNDM nuns

The municipality of Senator Ninoy Aquino is ready for tourism. What has made me say this? The availability of souvenir items. That’s my simple gauge. The natural wonders have always been there. Resorts and inns are sprouting. Cultural preservation is in place. And now tourists can buy trinkets that they can take home. All that is really missing is a serious effort to bring all these elements together, improve them, and present them to outsiders.

I’m not laying out here some grand tourism development scheme. I simply want to share the tribal beadworks that are for sale in Kulaman village, the poblacion of Senator Ninoy Aquino. The items are in the forms of necklaces, bracelets, pouches, and key fobs. As expected of indigenous artworks, they come in bright colors and simple geometric patterns. The key fobs cost P25 to P50 each, the bracelets more or less P50, the pouches P50 to P100, and the necklaces P50 to P300. You can buy them in Delesan Kailawan, a “cultural heritage home” maintained by the RNDM sisters, beside the Catholic school Notre Dame of Kulaman. A store across the main gate of the school also sells the items.

You may have your name embedded in the bracelets and other beaded items

The bead workers (Photo courtesy of RNDM nuns in Kulaman village)

Monday, November 16, 2015

Brief Histories of Lebak and Kalamansig

Municipality of Lebak

Lebak came into existence by virtue of Executive Order No. 82, dated August 18, 1947. Lebak was created from two municipal districts: the district of Lebak under the municipality of Kiamba, Cotabato (now Kiamba, Sarangani), and the district of Salaman under the municipality of Dinaig, Cotabato (now Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao).

Lebak is a Maguindanaon word that means “hollow.” It is used to refer to the place because in the eastern part of it are mountains and in the western part is the Celebes Sea.

Executive Order No. 432, dated April 12, 1951, transferred the seat of government of Lebak from Kalamansig to Salaman, Lebak.

Dulangan Manobos and Tedurays were the original inhabitants of the mountains, and Maguindanaons, who were Islamized in the sixteenth century, occupied the coastal area of present-day Tran and Datu Karon. The decades after World War II saw an influx of settlers from Visayas and Luzon. But years before, some Americans had already set up coconut plantations in Barurao and Tipudos.

The existence of various tribes in the area resulted to bloody conflicts. There was a Tiruray rampage in 1970 and a Muslim rebellion in 1973.

In August 1976, a strong earthquake hit Lebak and caused a tsunami. The wave swept almost all the houses in the village of Tibpuan. The people rose from the disaster and reconstructed the municipality.

Municipality of Kalamansig

The poblacion of Kalamansig today used to be the seat of government of the municipal district of Lebak. In 1951, Lebak became a municipality, and the seat of government was moved to another village. On December 29, 1961, the municipality of Kalamansig was created by virtue of Executive Order no. 459 of Pres. Carlos P. Garcia.

The name of Kalamansig came from the Dulangan Manobo phrase “Kulaman suwayeg,” which means “Kulaman in the water.” Kulaman was a chieftain who drowned in a river while trying to provide food for his family. The village where the chieftain died was named after him. In 1989, however, when the municipality of Senator Ninoy Aquino was created, Barangay Kulaman was removed from Kalamansig and became the poblacion of the new municipality.

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Lebak came into existence by virtue of Executive Order No. 82, dated August 18, 1947. Lebak was created from two municipal districts: the district of Lebak under the municipality of Kiamba, Cotabato (now Kiamba, Sarangani), and the district of Salaman under the municipality of Dinaig, Cotabato (now Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao).

Lebak is a Maguindanaon word that means “hollow.” It is used to refer to the place because in the eastern part of it are mountains and in the western part is the Celebes Sea.

Executive Order No. 432, dated April 12, 1951, transferred the seat of government of Lebak from Kalamansig to Salaman, Lebak.

Dulangan Manobos and Tedurays were the original inhabitants of the mountains, and Maguindanaons, who were Islamized in the sixteenth century, occupied the coastal area of present-day Tran and Datu Karon. The decades after World War II saw an influx of settlers from Visayas and Luzon. But years before, some Americans had already set up coconut plantations in Barurao and Tipudos.

The existence of various tribes in the area resulted to bloody conflicts. There was a Tiruray rampage in 1970 and a Muslim rebellion in 1973.

In August 1976, a strong earthquake hit Lebak and caused a tsunami. The wave swept almost all the houses in the village of Tibpuan. The people rose from the disaster and reconstructed the municipality.

Municipality of Kalamansig

The poblacion of Kalamansig today used to be the seat of government of the municipal district of Lebak. In 1951, Lebak became a municipality, and the seat of government was moved to another village. On December 29, 1961, the municipality of Kalamansig was created by virtue of Executive Order no. 459 of Pres. Carlos P. Garcia.

The name of Kalamansig came from the Dulangan Manobo phrase “Kulaman suwayeg,” which means “Kulaman in the water.” Kulaman was a chieftain who drowned in a river while trying to provide food for his family. The village where the chieftain died was named after him. In 1989, however, when the municipality of Senator Ninoy Aquino was created, Barangay Kulaman was removed from Kalamansig and became the poblacion of the new municipality.

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Friday, November 13, 2015

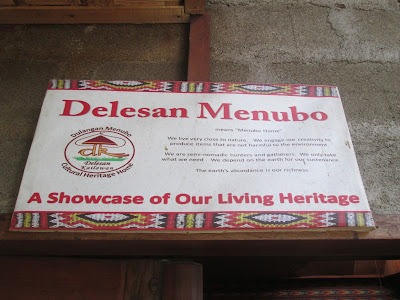

A ‘Cultural Heritage Home’

To the right is the entrance to the RNDM sisters' compound,

which has facilities for Dulangan Manobos.

I had been wishing Kulaman Plateau had something like a museum—a place that exhibits the traditional objects that the Dulangan Manobo people use. I was therefore delighted when I found out that such a place exists. It’s run not by the local government, as the case should ideally be, but by missionary Catholic nuns. It’s a little disappointing—though not wholly unexpected—to find out that religious and civic organizations still do more for indigenous people than the government does.

The Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions (RNDM) call the place Delesan Kailawan, which means “cultural heritage home.” It is situated beside Notre Dame of Kulaman, a school that offers basic education and run by the diocese. The Catholic Church and the priests’ compound are on the other side of the school. Delesan Kailawan is really a convent with added facilities for the Dulangan Manobo, especially women, who avail themselves of the scholarship grants, medical assistance, livelihood trainings, and other programs offered by the RNDM sisters. Sister Kikiwin and Sister Weeyyaa told me a few things about the work of their congregation, but I ought to go back there and ask them more about that. When I visited Delesan Kailawan, twice, I was pressed for time and I was too excited to see the Manobo objects and identify them.

The compound is indeed a home. Well-maintained gardens surround the structures. When you enter the gates, a paved footpath leads you to Tegasalibatun, a two-story “place of welcome.” The nuns who welcomed my companions and me came out of the building, so I assume it is where the nuns and their scholars stay. Beside Tegasalibatun is a one-room structure, which must be a chapel. Retrace your steps, but instead of going back to the gates, walk to a structure that looks like a classroom. It is partially hidden from the gates because the ground it is built on is slightly sunken. The room is Delesan Menubo, which literally means “Menubo home.” It is where the tribal objects are found. It was my main destination. I spent a long time inside it during my visits, taking photos and identifying the displayed objects (which have not been labeled yet) with the help of the Manobo scholars who were around.

Attached to Delesan Menubo is a large shed made of wood and kalakat (weaved African palm). It’s Keseteponoy, which means “gathering.” It’s where meetings, trainings, and related activities are conducted. During my visits, I noticed a few Manobo women and their children coming from the direction of Keseteponoy and peeking at me and the Manobo girls in the Delesan Menubo, curious about what we were doing there. The Manobo girls told me that the women and children were patients. One toddler had two deep gashes on her head which probably started as mere itchy spots. There was apparently a clinic inside the compound. But I didn’t see the clinic. All I can share with you now are photos of Tegasalibatun, Delesan Menubo, and Keseteponoy. As to the traditional Manobo objects, I’ll share their photos with you next year, a few months from now, after I’ve checked and rechecked their names.

which has facilities for Dulangan Manobos.

I had been wishing Kulaman Plateau had something like a museum—a place that exhibits the traditional objects that the Dulangan Manobo people use. I was therefore delighted when I found out that such a place exists. It’s run not by the local government, as the case should ideally be, but by missionary Catholic nuns. It’s a little disappointing—though not wholly unexpected—to find out that religious and civic organizations still do more for indigenous people than the government does.

The Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions (RNDM) call the place Delesan Kailawan, which means “cultural heritage home.” It is situated beside Notre Dame of Kulaman, a school that offers basic education and run by the diocese. The Catholic Church and the priests’ compound are on the other side of the school. Delesan Kailawan is really a convent with added facilities for the Dulangan Manobo, especially women, who avail themselves of the scholarship grants, medical assistance, livelihood trainings, and other programs offered by the RNDM sisters. Sister Kikiwin and Sister Weeyyaa told me a few things about the work of their congregation, but I ought to go back there and ask them more about that. When I visited Delesan Kailawan, twice, I was pressed for time and I was too excited to see the Manobo objects and identify them.

The compound is indeed a home. Well-maintained gardens surround the structures. When you enter the gates, a paved footpath leads you to Tegasalibatun, a two-story “place of welcome.” The nuns who welcomed my companions and me came out of the building, so I assume it is where the nuns and their scholars stay. Beside Tegasalibatun is a one-room structure, which must be a chapel. Retrace your steps, but instead of going back to the gates, walk to a structure that looks like a classroom. It is partially hidden from the gates because the ground it is built on is slightly sunken. The room is Delesan Menubo, which literally means “Menubo home.” It is where the tribal objects are found. It was my main destination. I spent a long time inside it during my visits, taking photos and identifying the displayed objects (which have not been labeled yet) with the help of the Manobo scholars who were around.

Attached to Delesan Menubo is a large shed made of wood and kalakat (weaved African palm). It’s Keseteponoy, which means “gathering.” It’s where meetings, trainings, and related activities are conducted. During my visits, I noticed a few Manobo women and their children coming from the direction of Keseteponoy and peeking at me and the Manobo girls in the Delesan Menubo, curious about what we were doing there. The Manobo girls told me that the women and children were patients. One toddler had two deep gashes on her head which probably started as mere itchy spots. There was apparently a clinic inside the compound. But I didn’t see the clinic. All I can share with you now are photos of Tegasalibatun, Delesan Menubo, and Keseteponoy. As to the traditional Manobo objects, I’ll share their photos with you next year, a few months from now, after I’ve checked and rechecked their names.

Tegasalibatun, where the RNDM sisters and their female Manobo scholars stay

A chapel beside Tegasalibatun

Delesan Menubo, the room where Manobo items are on display

The Manobo girsl who helped me identify the objects in Delesan Menubo.

As I read the items in my prepared list, they pointed the samples to me.

Keseteponoy, where trainings and meetings are held

Monday, November 9, 2015

Palimbang: Map and Facts in Brief

Land area: 84,370 hectares

Population: 117,529 (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

Number of barangays: 40

Literacy rate: 70.08 % (household population 10 years old and above, 2000)

Population density: 244 persons per sq. km. (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

No. of households: 23,913 (projected for 2013, based on 2007 census)

Major industry: farming, fishing

Major crops: rice, corn, coconut, fish

Scenic spots: Alidama Island, Seven Lakes

Income: 130.33 million (2010)

Registered voters: 38,027 (2010)

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Population: 117,529 (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

Number of barangays: 40

Literacy rate: 70.08 % (household population 10 years old and above, 2000)

Population density: 244 persons per sq. km. (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

No. of households: 23,913 (projected for 2013, based on 2007 census)

Major industry: farming, fishing

Major crops: rice, corn, coconut, fish

Scenic spots: Alidama Island, Seven Lakes

Income: 130.33 million (2010)

Registered voters: 38,027 (2010)

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Friday, November 6, 2015

A Cave in a School

Going into the cave inside Senator Ninoy Aquino National High School

requires some contortion skills.

As stated so many times in this blog, Kulaman Plateau has a hundred caves. You can find them in the usual places as well as in the unexpected ones. So perhaps it is not surprising that there’s a small cave inside the campus of Senator Ninoy Aquino National High School, right in the center of the town.

When I dropped by the school on October 20, I grabbed the chance of course to take a look at the cave. I asked a teacher to ask some students to guide me. It was examination day that time, and many students were loitering inside the campus in between exams, so the teacher asked a group of girls to accompany me. I swear that I didn’t lead the girls astray, away from attaining proper education. The cave is just about thirty meters from the nearest classroom and the ground where flag ceremonies are conducted every morning.

The passage inside was covered to prevent students from exploring–and

disappearing into–the cave

The mouth of the cave is very small, just a little more than a meter high and about half a meter wide. The ground in front of the cave’s mouth dips a little, and everyone except me was afraid to walk past the elevated portion. I asked my brother—who was with me, by the way—to stand in front of the cave’s mouth so that I could take a photo of the mouth with a person. I wanted the photo to show the size of the hole compared to a person. My brother refused. I asked the girls. They refused too. Some curious boys by this time had joined us. I asked them. They refused. They were all afraid of snakes or evil spirits that might be lurking behind the crevice. I had no choice in the end but to give the camera to my brother and stand in front of the cave myself.

I stuck my head into the hole and took photos of what was inside. It was a small cave indeed, as people had told me. You couldn’t stand straight inside it. The chamber near the entrance must be connected to bigger chambers, for the cave and half of the campus stood on top of a hill, which might be hollow under. I couldn’t verify this because the passage was sealed with clumps of soil, uprooted weeds, and a large plastic bin. It might have been done on purpose to prevent students from exploring the cave. But if all the students of the school were like the ones who accompanied me, the administration had nothing to worry about. We stayed in the premises of the cave for less than ten minutes.

Limestone juts out of the campus ground. Water might have eroded

through time the stone underneath and formed caves.

Monday, November 2, 2015

Bagumbayan: Map and Facts in Brief

Land area: 59,300 hectares

Population: 59,810 (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

Number of barangays: 19

Creation: June 21, 1969, Republic Act No. 5960, from Isulan

Literacy rate: 86.66 % (household population 10 years old and above, 2000)

Population density: 101 persons per sq. km. (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

No. of households: 12,620 (projected for 2013, based on 2007 census)

Major industry: farming, mining

Major crops: rice, corn, coffee, banana, pineapple, sunflower

Registered voters: 31,089 (2010)

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Population: 59,810 (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

Number of barangays: 19

Creation: June 21, 1969, Republic Act No. 5960, from Isulan

Literacy rate: 86.66 % (household population 10 years old and above, 2000)

Population density: 101 persons per sq. km. (projected for 2012, based on 2007 census)

No. of households: 12,620 (projected for 2013, based on 2007 census)

Major industry: farming, mining

Major crops: rice, corn, coffee, banana, pineapple, sunflower

Scenic spots: Pitot Cave in Sto. Niño, Bamban Falls in Kapaya, Guano Cave in Masiag, hot spring in Daguma, banana plantations in Sumilil, waterfall in Bai Saripinang, waterfall in Kinayao, Mercy Rose Swimming Pool in Sison, Hidden Spring Resort in Tuka, Maetas Cave in Titulok

Income: 285.60 million (2010)Registered voters: 31,089 (2010)

(Blogger’s note: This post is a part of “The Other Towns” series. See my October 5 post for the overview.)

Sunday, November 1, 2015

Three Days in Kulaman Village

I was finally able to stay in Barangay Kulaman for a while. From October 20 to 22, my brother and I visited our mother in the poblacion. She had been reassigned there as principal of the national high school since July. Our father joined us on the twenty-second, and I left for the capital town on the twenty-third. I spent three days only in the central village, but it was so far the longest I had stayed there.

I never got to visit for long the poblacion because for the residents of my home village, it is more convenient to head straight to the capital town of the province when transacting businesses. The poblacion is west of my home village, and the capital town is in the east. The difference in the fare isn’t much, and the road to the poblacion is worse than the road to the capital town. So normally, the people in my village only go to the poblacion if they have to process documents in the municipal hall.

Though my visit in Barangay Kulaman was short, I was able to accomplish there two weeks’ worth of tasks. In the coming weeks, I’ll devote a post each for the most important ones. For now, here’s the overview.

October 20, Tuesday

At 8:30 AM, my brother and I ride a skylab from our home village to the poblacion. We ask the driver to drop us at the national high school because we can’t remember where exactly our mom is staying. We knew beforehand that we would not be a disturbance in the school because it’s the last day of their periodical exams and an interschool athletic meet that the school is hosting is starting the next day. There’s no regular class. For half an hour or so, my bro and I eat lanzones in a corner in our mom’s office. I then ask some students who are chatting on a bench to show me the tiny cave inside the campus.

At noon, our mom takes my bro and me to the house where she’s staying, which is also a house of our relative. My phone rings at about one in the afternoon. The caller informs me that I’m one of the finalists in the F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. I’m surprised and delighted, but the problem is that the awarding ceremonies will be on the coming Monday. I tell the caller that I’m currently very far from Manila and could not possibly make it to the event. He tells me my fare for the flight and the hotel accommodation will be sponsored. I tell him all right, I’ll be there.

With my brother, I go to the compound of Catholic nuns to see the Dulangan Manobo objects that are on display in one of the structures there. I realize I forgot to bring the list of Manobo things that I have prepared. I have no easy way of knowing the names of the displayed items. I've left the list because I’ve been thinking how to book a flight to Manila here in the middle of nowhere. I content myself with just taking photos.

I learn from my mom’s colleagues that one of them has a ticketing business and there’s already an internet café in town. It means that I no longer have to “go down” to the capital town the next day to make arrangements for my travel and to keep on communicating with F. Sionil Jose’s daughter, who called me after the guy from Philippine PEN did.

October 21, Wednesday

I start the day with a hot drink made from powdered marang seeds in the house of my uncle, my mom’s landlord. Marang, which looks like a cross between jackfruit and durian, is a common fruit in Mindanao, but it’s my first time to take it in a drink form, a la hot coffee. The seeds were dried and ground, and the powder looks and tastes so much like soybeans.

When my bro wakes up, I ask him to go with me to Kulaman River to bathe. Our four-year-old niece tags along and acts as our guide. The little girl and I bathe. My brother doesn’t. The girl loves the water, and my bro and I have a hard time persuading her to get out of it to go back home.

In the afternoon, my bro and I spend a few hours in the only Internet café in town. The café has six or seven computers only, and customers often have to wait for fifteen minutes to more than an hour before a station is vacated. Later, we eat batchoy in a stall and watch the parade of athletes. Five zones from the towns of Senator Ninoy Aquino and Bagumbayan will be competing against one another in the next two days; the winning teams will then represent the unit in the provincial meet in November. The batchoy, at best, tastes all right. Local cuisine is one thing that still needs to be developed in Kulaman Plateau.

October 22, Thursday

I was told the previous day that there’s a busay, or waterfall, near the river, so I decide to check it out with my brother. There’s a waterfall right beside the river, but it’s just more than a meter high and the water isn’t much stronger than a trickle. I deduce that the waterfall I was told about is behind the tiny waterfall, hidden by tall weeds. To see the hidden waterfall, I have to cross the river, climb the tiny waterfall, and walk the narrow path behind. I try going to the opposite bank, but I can’t find a spot that is shallow enough to wade through. I have to swim. I decide to abandon the plan. I’m afraid to swim because I can only do it in steady waters and short distances and because I’m not familiar with the river’s current and all.

My bro and I go back to the nuns’ compound because I have to make more-detailed notes on the Manobo objects displayed there. Because I’m no longer distracted, worrying about how to book a flight, my second visit to the compound turns out to more productive. With the help of some Manobo high school students, I’m finally able to identify most of the items listed in the Kitab (Customary Law) of the Dulangan Manobo.

I finally get my plane ticket at noontime. I ride a motorcycle to my home village to get a traveling bag and some pairs of shoes. The travel to my village and then back to the poblacion takes about an hour and a half. I can clearly see that the haze coming from the forest fires in Indonesia is getting worse. It looks as though there’s rain on the hills in the distance, but I’m sure that there’s no rain because there are no massive dark clouds in the sky. The sky—and indeed, the world—is covered in gray.

I’m writing more-detailed accounts of my trip to Kulaman Village, and I’m posting them every Friday for the next several weeks. This “Three Days in Kulaman” series will run parallel with “The Other Towns” series, which started last month and appears every Monday.

I never got to visit for long the poblacion because for the residents of my home village, it is more convenient to head straight to the capital town of the province when transacting businesses. The poblacion is west of my home village, and the capital town is in the east. The difference in the fare isn’t much, and the road to the poblacion is worse than the road to the capital town. So normally, the people in my village only go to the poblacion if they have to process documents in the municipal hall.

Though my visit in Barangay Kulaman was short, I was able to accomplish there two weeks’ worth of tasks. In the coming weeks, I’ll devote a post each for the most important ones. For now, here’s the overview.

This is how big the mouth of SNANHS cave is compared to a person.

Please bear with the model. His better-looking companions

didn't want to stand near the hole themselves because something

might shoot out of the hole and bite or snatch them.

October 20, Tuesday

At 8:30 AM, my brother and I ride a skylab from our home village to the poblacion. We ask the driver to drop us at the national high school because we can’t remember where exactly our mom is staying. We knew beforehand that we would not be a disturbance in the school because it’s the last day of their periodical exams and an interschool athletic meet that the school is hosting is starting the next day. There’s no regular class. For half an hour or so, my bro and I eat lanzones in a corner in our mom’s office. I then ask some students who are chatting on a bench to show me the tiny cave inside the campus.

At noon, our mom takes my bro and me to the house where she’s staying, which is also a house of our relative. My phone rings at about one in the afternoon. The caller informs me that I’m one of the finalists in the F. Sionil Jose Young Writers Awards. I’m surprised and delighted, but the problem is that the awarding ceremonies will be on the coming Monday. I tell the caller that I’m currently very far from Manila and could not possibly make it to the event. He tells me my fare for the flight and the hotel accommodation will be sponsored. I tell him all right, I’ll be there.

With my brother, I go to the compound of Catholic nuns to see the Dulangan Manobo objects that are on display in one of the structures there. I realize I forgot to bring the list of Manobo things that I have prepared. I have no easy way of knowing the names of the displayed items. I've left the list because I’ve been thinking how to book a flight to Manila here in the middle of nowhere. I content myself with just taking photos.

I learn from my mom’s colleagues that one of them has a ticketing business and there’s already an internet café in town. It means that I no longer have to “go down” to the capital town the next day to make arrangements for my travel and to keep on communicating with F. Sionil Jose’s daughter, who called me after the guy from Philippine PEN did.

Inside the Dulangan Manobo “cultural heritage home” run by Catholic nuns

October 21, Wednesday

I start the day with a hot drink made from powdered marang seeds in the house of my uncle, my mom’s landlord. Marang, which looks like a cross between jackfruit and durian, is a common fruit in Mindanao, but it’s my first time to take it in a drink form, a la hot coffee. The seeds were dried and ground, and the powder looks and tastes so much like soybeans.

When my bro wakes up, I ask him to go with me to Kulaman River to bathe. Our four-year-old niece tags along and acts as our guide. The little girl and I bathe. My brother doesn’t. The girl loves the water, and my bro and I have a hard time persuading her to get out of it to go back home.

In the afternoon, my bro and I spend a few hours in the only Internet café in town. The café has six or seven computers only, and customers often have to wait for fifteen minutes to more than an hour before a station is vacated. Later, we eat batchoy in a stall and watch the parade of athletes. Five zones from the towns of Senator Ninoy Aquino and Bagumbayan will be competing against one another in the next two days; the winning teams will then represent the unit in the provincial meet in November. The batchoy, at best, tastes all right. Local cuisine is one thing that still needs to be developed in Kulaman Plateau.

Morning dip in Kulaman River with my niece

October 22, Thursday

I was told the previous day that there’s a busay, or waterfall, near the river, so I decide to check it out with my brother. There’s a waterfall right beside the river, but it’s just more than a meter high and the water isn’t much stronger than a trickle. I deduce that the waterfall I was told about is behind the tiny waterfall, hidden by tall weeds. To see the hidden waterfall, I have to cross the river, climb the tiny waterfall, and walk the narrow path behind. I try going to the opposite bank, but I can’t find a spot that is shallow enough to wade through. I have to swim. I decide to abandon the plan. I’m afraid to swim because I can only do it in steady waters and short distances and because I’m not familiar with the river’s current and all.

My bro and I go back to the nuns’ compound because I have to make more-detailed notes on the Manobo objects displayed there. Because I’m no longer distracted, worrying about how to book a flight, my second visit to the compound turns out to more productive. With the help of some Manobo high school students, I’m finally able to identify most of the items listed in the Kitab (Customary Law) of the Dulangan Manobo.

I finally get my plane ticket at noontime. I ride a motorcycle to my home village to get a traveling bag and some pairs of shoes. The travel to my village and then back to the poblacion takes about an hour and a half. I can clearly see that the haze coming from the forest fires in Indonesia is getting worse. It looks as though there’s rain on the hills in the distance, but I’m sure that there’s no rain because there are no massive dark clouds in the sky. The sky—and indeed, the world—is covered in gray.

I’m writing more-detailed accounts of my trip to Kulaman Village, and I’m posting them every Friday for the next several weeks. This “Three Days in Kulaman” series will run parallel with “The Other Towns” series, which started last month and appears every Monday.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)